Main navigation

Researched and Written by

Dr. Fred Stamler

Emory Warner was a native of rural Williamsburg, Iowa, who received his medical degree in Iowa City in 1929. His interest in Pathology was stimulated in his senior year by Dr. George Whipple’s visit to Iowa City as a guest lecturer. Dr. Whipple expressed a desire to interview a student who might be interested in a career in Pathology, and Emory Warner was selected by the Dean as a likely candidate. Dr. Whipple was favorably impressed, and offered an internship appointment for the following year. Dr. Warner promptly accepted, although this necessitated his resignation from a rotating internship already arranged elsewhere.

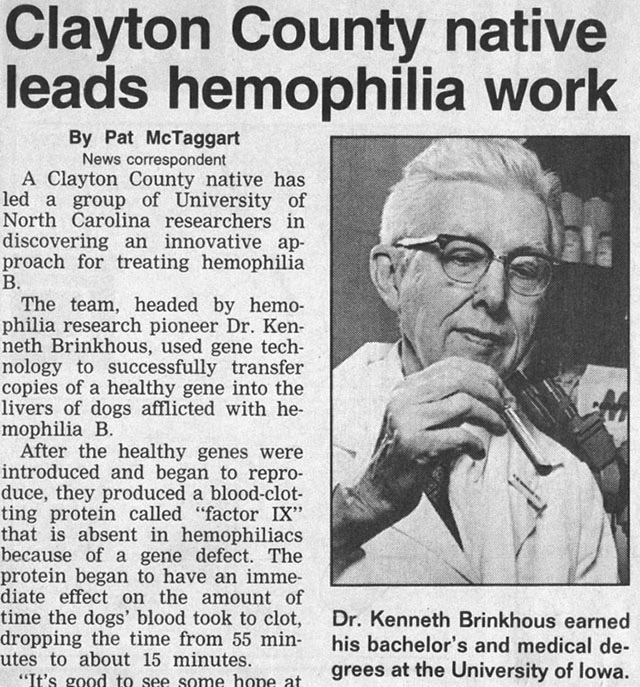

When Emory Warner became head of the critically depleted war time department in 1945, he was the only remaining member of the original group which had put Iowa in the forefront of research in blood coagulation. Walter Seegers had departed in 1944 to head the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at Wayne State University in Detroit, where he continued to compile a distinguished record in coagulation research until and beyond retirement. Kenneth Brinkhous was called to army duty in 1941. He attained the rank of Lt. Colonel in the medical corps before returning briefly to the Department in 1945. In 1947 he left to become Head of Pathology at the University of North Carolina where he gained worldwide recognition for his continuing studies of hemophilia and other aspects of coagulation research.

Staff replacements were difficult to recruit at war’s end. John R. (Jack) Carter, a University of Rochester graduate (1943) and former Whipple student fellow joined the Iowa staff in 1944, but his stay was interrupted by two years of military service in 1946. Eugene Boyd came to the Department as an assistant in 1940, only to leave for army service in 1942. He returned to the department in 1945, and resigned in 1952 to accept the newly created position of Chief of Pathology at Mercy Hospital in Iowa City. Willard Pheteplace began residency training in 1942, and left to enter private practice of Pathology in Davenport in 1945. George Chambers, a wartime student fellow, graduated from the medical college and departed from Iowa City in 1946. Jack Layton and Fred Stamler returned from military service in 1948 to join the Department with the goal of pursuing academic careers in Pathology.

Prior to World War II much of the routine surgical and autopsy pathology service had been done by surgery residents on one-year assignments as Assistants in Pathology. During the war residency programs in Surgery were drastically curtailed and time spent in Pathology was reduced, never to be restored to the one-year allotment. Other departments augmented the Pathology work force to variable degrees. Residents in Orthopaedics, Urology, Otolaryngology, and Neurosurgery at various times were assigned to Pathology for periods of from three to six months. Prospective Radiology residents were encouraged by Radiology Head, Dr. Dabney Kerr, to work as Pathology Assistants for a year. Their eventual acceptance by Radiology was conditional upon satisfactory performance in Pathology. John Sulzbach (1946-47), Mansfield Lagen (1946-47), Gwilyn Lodwick (1947-48) and William Gladstone (1949-50) were notable examples of this system who all went on to successful careers in Radiology. George Bedell (1947-48, Malcolm Campbell (1948-49) and Roy Phillips (1948-49) utilized a year in Pathology as prelude to residency in Internal Medicine.

A formal residency program such as that currently in operation did not exist in the Department in the early post World War II years. Those individuals professing an interest in Pathology as a career usually began with the title of Assistant, and rose through the ranks as Instructor and Associate before attaining rank as Assistant Professor. The emphasis was mainly in the area of Anatomic Pathology and teaching, since the subspecialty of Clinical Pathology was still in a formative stage.

The impetus for recognition and certification of specialists in Clinical Pathology came from private practice and hospital pathologists rather than academicians. The American Society of Clinical Pathologists (ASCP) was conceived at a small gathering of practicing pathologists in St. Louis in 1922. The American Journal of Clinical Pathology (AJCP) began publication in 1931 as the official organ of the ASCP. The presidential address at the ASCP meeting, published as the lead article of the first issue of the AJCP lamented the lowly position of the hospital pathologist, financially and otherwise, with suggestions for remedial action. Four years later (1935) the then current president of ASCP, Dr. Arthur H. Sanford, advocated the formation of Specialty Boards in Pathology. The Society concurred, and by 1936 had taken steps to gain approval from the AMA Advisory Board of Medical Specialists. The Directory of Medical Specialties of 1940 published full information about requirements for admission to the specialties of Anatomical and Clinical Pathology. These subspecialties were defined much as now accepted, and applicants could apply for admission to either or both categories. Admission standards were gradually refined and standardized, and in 1947 the Board announced that after January 1, 1948, all applicants must take an examination given by the Board. In 1950 the Board announced that after July 1, all AP-CP applicants must have two years supervised training in CP. This deadline was apparently later extended to July 1, 1953. In the meantime, more comprehensive criteria were being developed for approval of training facilities and practices, in conjunction with the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals of the AMA. By the middle 1950’s the summation of these criteria required several pages of close print in the Board Directory. Since that time, further refinements have been added, and the number and diversity of subspecialties within the two main subdivisions of AP and CP continue to increase impressively.

The academic structure of the Iowa College of Medicine and University Hospitals, like most academic medical centers, was poorly designed to enable the Pathology Department to cope with the demands put upon it by the post World War II burgeoning of Clinical Pathology. Since the beginning of the Department it had performed a major role in undergraduate teaching and autopsy and surgical pathology. With the advent of H.P. Smith in 1930, it had become first class in experimental Pathology. In contrast to its recognized status in basic anatomical and experimental pathology, it had little to offer in clinical pathology. Bacteriology had become a separate department, and clinical chemistry, serology, immunology, blood banking, and hematology facilities were scattered about the hospital complex under control of several different departments, including Internal Medicine, Biochemistry, and the State Hygienic Laboratory. These departments were understandably reluctant to relinquish control of laboratories which they had developed and continued to staff. They usually were equally reluctant to accept arrangements whereby their facilities could be utilized in the operation of a workable Clinical Pathology residency program.

In spite of all obstacles, the Pathology department did gain approval for both AP and CP residency training programs. Approval for CP training was gained by forming working agreements with other departments for residency involvement in clinical chemistry, hematology, serology, and microbiology. Although this situation was not very attractive to CP residents, a limited number of AP-CP residents qualified and became board certified during the 1960’s. These included Arnold Tammes (1958-67), Herbert Miller (1964), Barry Knapp (1964), James Smith (1965), James Robertson (1967), Daniel Till (1969), Paula Arnell (196), John Lyday (1969), Wayne Phillips (1969) and Robert Cardelli (1969). During those years, a number of recruits elected to follow the anatomic course only, some with academic goals in mind. These included William Smith (1949-53), Albert Hilberg (1949-51), George Zimmerman (1951-71), James J. Butler (1953-57), Franz Enzinger (1954-58), Carleton Nordschow (1954-70), Fernando Aleu (1957-62), Robert Givler (1957-61), John Davis (1960-67), Daniel Longnecker (1959-69), Thomas Kent (1961-95), Dale Huff (1963-65), Michael Korns (1963-70), Cooley Butler (1966-68) and Steven Bauserman (1969-73). A majority of these residents filled academic positions at Iowa or elsewhere after completion of their residency.

During the 1960’s the clinical laboratory facilities gradually came more under the direction of the Pathology Department. This made possible better coordination of all phases of the residency program, although serious space and staffing problems still existed, and continued to exist well into the next decade.

The problems faced by Pathology in the post-war years were by no means unique to the department, but tended to be shared by all units of the medical college and University Hospitals. Greatly increased demands on clinical and laboratory medicine made academic budgets woefully inadequate. Faculty and staff were depleted by the war and the hospital had undergone no expansion and very niggardly maintenance since its opening in 1928. State funds for capitol improvements and increased salary budgets were not forthcoming. University President Hancher recognized the gravity of the situation and instructed Dean MacEwen to provide a solution. A plan to augment salaries was given highest priority, and Dean MacEwen’s initial response to the charge was rather prompt. It met strong opposition from some medical faculty, especially clinical department heads who would no longer be allowed to monopolize private practice fees in their departments. The solution to this state of conflict was complicated by Dean MacEwen's failing health and eventual death from a heart attack on September 2, 1947.

Dr. Warner was a member of a committee involved in the planning and implementation of the Compensation Plan at the time of Dean MacEwen’s death.

This committee of five members then became an Executive Committee to administer the affairs of the medical college until a new dean could take office. In spite of all opposition, a plan was approved by President Hancher and the Board of Regents and was put into operation on a trail basis on July 1, 1947. This Medical Service Plan, with frequent reviews, and continuing modifications, remains in effect, and has been a major factor in the tremendous growth and development of the University Hospitals. Many of those involved in this origin and early operation would agree with Dean Robert Hardin’s later expressed opinion that "the plan saved the Medical College."

Dr. Mayo Soley became medical dean in 1948. He had become sufficiently impressed with the work of the Executive Committee that he requested that the members continue as his advisory committee. After Dean Soley’s death on June 21, 1949, this group again became an Executive Committee. Their management of medical college problems impressed the medical faculty sufficiently that many of the faculty favored indefinite or permanent continuance of this form of administration. The appointment of Norman Nelson as Dean in 1953 again placed the committee in an advisory role, and some form of "Executive Committee" has continued to be an integral part of medical college administration at Iowa since that time.

The critical shortage of space and associated physical facilities of the entire university was a continuing frustration during the first and second post-war decades. The new Veterans Administration Hospital, completed in 1952, provided additional facilities accompanied by increased demands. The federally subsidized Medical Research Center, constructed in 1957, alleviated but did not eliminate the critical shortage of research space. The Basic Science Building in 1972 finally provided the space for development of modern departments of pre-clinical medicine. The passage of the Medicare Act put enormous pressure on the hospital, because governmental regulations now decreed most of the hospital beds to be inadequate to meet requirements for patient care reimbursement. A state policy of bonded indebtedness was instituted to finance hospital revisions and additions to bring it into conformity with regulations and this policy has continued to date. Pathology has been a rather late beneficiary of that policy. One important result of this process over the years has been a shift in cost of patient care from the state to federal government and the patient.

Departmental research activities continued during the post-war years, with gradually diminishing emphasis on blood coagulation, Warner and Carter continued to be very active in that field until Carter left in 1960. Warner’s interest later turned to the interdepartmental research center for atherosclerosis and thrombosis which had been developed at Iowa, and he contributed materially to the success of that group effort. Jack Layton developed interest in viral and Rickettsial diseases, and basic electron microscopy. Stamler studied animal models of pregnancy diseases, and reported original observations of fatal disseminated intravascular coagulation (toxemia of pregnancy) in pregnant rats subjected to Vitamin E deficient diets. A wide range of interests were favored by other departmental members, including physical chemistry of connective tissues (Nordschow), cardiac pathology (Korns), gastrointestinal diseases (Kent), pancreatic diseases (Longnecker), gynecological malignancies (Levine), wound healing and lathyrism (Enzinger). Kent later made valuable contributions to medical education practices by innovative approaches to methodology and assessment of teaching effectiveness.

Emory Warner had continuously heavy demands upon his time and energy, both within and beyond departmental confines. He was always an active teacher at all levels, popular with students, and appreciated by house staff and colleagues, as well as those outside the academic fold. The Iowa Association of Pathologists had received his support from its origin in the early 1930’s , and had shown its appreciation by later electing him to life membership. He continued to serve on important collegiate committees, including the Deans Committee for the Veterans Administration Hospitals in Iowa City and Des Moines. He served conscientiously on Review Committees for the National Institute of Health, and was elected to a term as president of the American Society of Experimental Pathologists in 1957. The Gold Headed Cane of the American Society of Pathologists was awarded him in 1980. This award is generally considered to be the highest award given by organized Pathology to a member.

Dr. Warner was always supportive of his staff, and took much satisfaction from the fact that significant numbers became departmental heads or attained other positions of prominence. Those becoming heads of academic departments include John R. Carter (Kansas) later Case Western Reserve at Cleveland, Jack M. Layton (Arizona), Jon V. Straumfjord (Wisconsin at Milwaukee), and Carlton D. Nordschow (Indiana), followed by James Smith after Nordschow’s retirement. Others of note include Franz Enzinger, whose work at the AFIP made him a world famous authority on soft tissue tumors, and James J. Butler of M.D. Anderson Hospital in Houston, a leader in hematopathology.

Dr. Warner retired as department head in 1970, and left Iowa City in order that he might not appear to exert undue influence upon departmental activities. He later returned to part-time duty in the department, at the cordial invitation of Dr. George Penick and the entire staff of the department. For several years he divided his time between part-time assignments at Arizona and Iowa City, until a few months before his death from cancer (hypernephroma) in November, 1982, at the age of 77. His death negated plans to entertain him as the guest of honor at the dedication of the newly completed Emory Dean Warner Clinical Laboratories of the University Hospital, a fitting tribute to his long years of service to the institution.